Episode Seven: Ayesha Hameed and Sara Garzón

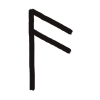

þ thorns þ

In this episode, Ayesha and Sara discuss the intersection of coloniality, indigenous knowledges and new media technologies, with a focus on climate catastrophe from a historical perspective.

This episode is a conversation between Ayesha Hameed and Sara Garzón. Ayesha is an artist whose work explores contemporary borders and migration, critical race theory, Walter Benjamin, and visual cultures of the Black Atlantic. Sara is a Colombian curator and art historian. She specializes in contemporary Latin American art, and focuses on issues relating to decoloniality, temporality, and indigenous eco-criticism. They discussed the intersection of coloniality, indigenous knowledges, and new media technologies, with a focus on climate catastrophe from a historical perspective. They talk about the representation of nature and the environment in colonial times. And they also examine the concept of eco-futurism in contemporary art, as well as the notion of interspecies collaboration.

Find out more about Ayesha and Sara on our People page.

To the Glossary Ayesha donates Subaquatic  and Sara donates chrononostalgia

and Sara donates chrononostalgia  .

.

This series is produced and edited by Hester Cant.

The series is co-curated by Emma McCormick-Goodhart and Martin Hargreaves, with concept and direction by Martin Hargreaves and Izzy Galbraith.

TRANSCRIPT:

MARTIN

Hello, you're listening to þ thorns þ, a podcast where we bring you conversations between artists in relation to concepts of the choreographic.  thorns

thorns  is produced as part of the Rose Choreographic School at Sadler's Wells. I'm Martin Hargreaves, head of the Rose Choreographic School, which is an experimental research and pedagogy

is produced as part of the Rose Choreographic School at Sadler's Wells. I'm Martin Hargreaves, head of the Rose Choreographic School, which is an experimental research and pedagogy  project. Across a two-year cycle, we support a cohort

project. Across a two-year cycle, we support a cohort  of artists to explore their own choreographic inquiries

of artists to explore their own choreographic inquiries  , and we also come together to imagine a school

, and we also come together to imagine a school  where we discover the conditions we need to learn from each other.

where we discover the conditions we need to learn from each other.

As part of the ongoing imagination of the school, we are compiling a glossary of words that artists are using to refer to the choreographic  . Every time we invite people to collaborate with us, we also invite them to donate to the glossary which is hosted on our website. There is a full transcript available for this episode on our website, together with any relevant links to resources mentioned.

. Every time we invite people to collaborate with us, we also invite them to donate to the glossary which is hosted on our website. There is a full transcript available for this episode on our website, together with any relevant links to resources mentioned.

This episode is a conversation between Ayesha Hameed and Sara Garzón. Ayesha is an artist whose work explores contemporary borders and migration, critical race theory, Walter Benjamin, and visual cultures of the Black Atlantic. Sara is a Colombian curator and art historian. She specializes in contemporary Latin American art, and focuses on issues relating to decoloniality, temporality, and indigenous eco-criticism.

For this conversation, Sara was in a studio in New York and Ayesha in London. They discussed the intersection of coloniality, indigenous knowledges, and new media technologies, with a focus on climate catastrophe from a historical perspective. They talk about the representation of nature and the environment in colonial times. And they also examine the concept of eco-futurism in contemporary art, as well as the notion of interspecies collaboration. As part of this conversation, you'll hear Ayesha and Sara share sound excerpts with each other. These sounds come from past and ongoing projects, and they will describe and speak in detail about them.

There are also more details in the resources linked in the episode description.

SARA

In my work, as I research the kind of intersections of coloniality, indigenous ecocriticism, and new media technologies, I've stumbled upon the world of climate catastrophe in a historical sense. My research specifically looks at this kind of watershed moment of 1992 and the quincentennial celebration of the discovery of America.

AYESHA

Mhm.

SARA

It has been through that work that I have done a little bit of, more kind of, transhistorical analysis of the last 500 years. Precisely because the events of 1992 had everything to do about the characterizations of the events of 1492, and this struggle for memory, right? In a moment in which we're seeing the end of the Cold War, and the kind of reshaping of a new global order. And in encountering some of this kind of colonial literature that was, of course, so much more relevant, or became heightened in the end of the1980s and the beginning of the 1990s, I found this incredible kind of anecdote from a historian, Jesús Carrillo Castillo, who recounted how, of course, ideas of climate change and catastrophe were not unique to our time, we know that. But, there was a particular instance, actually, in Spain in 1524, in which a close advisor to the Catholic Roman Empire, the Spanish crown, specifically to Charles I, his name was Federico Enriquez, made it, like, rampantly known that the environmental decline that had then, at the moment, in the 16th century, occasioned so many dramatic droughts, famines, earthquakes, and floods, and that, of course, also saw widespread peasant revolts around and throughout Europe, signalled the end of time.

Enriquez, moreover, was not alone in this apocalyptic interpretations of his current events, right? The events of 1524. He also pointed that his voice was among many prophets and astrologers all over Europe, who were, quote unquote, predicting that these major catastrophes would coincide with the conjunction in the planets of Pisces that year.

AYESHA

Mhm, mhm.

SARA

And this apocalyptic views of nature and social upheaval, of course, undermined the Spanish's crown possibility for expansion. And it was at this moment that their response, not only to the wake of end of the world scenarios and catastrophes, but specifically to their weakening in public perception, that they decided that, uh, what was needed was a redefinition of people's relationship to the environment, uh, through relatable images of nature.

And according to Jesús Carillo Castillo, I mean, this entire anecdote had to do with explaining as to what, to some degree, the reasons that kind of gave origin to the first botanical expeditions to the Americas.

AYESHA

Wow, okay.

SARA

And to a series of infrastructures around scientific knowledge. And kind of the redistribution of the sensible vis a vis the noble world. But looking at America as the site of the future, as a site of biodiversity and, yep, just kind of abundance. That it was seen as the opposite of Europe in a moment of absolute scarcity and climatic transformation.

AYEHSA

So literally the new world.

SARA

Mhm, exactly! Exactly. The new world. The beginning of the new world. And so, in the studies of Latin American futurity as we've seen it kind of played out in contemporary art. It seemed to me it had longer origins than the last three decades. It actually had the origin of this continuous reiteration of America, and the Americas as the site of the future. And yet the future did not mean this moment of, like the utopian becoming, right? It wasn't this moment to be in the future, right? It wasn't a day to come. This is something that Enrique Dussel, who's a decolonial scholar and historian himself, explained also in a very prominent book published in 1994 called El encubrimiento del Otro, right? The, uh, the concealing of the other. Alot, a part of this kind of literature. And in the book, Enrique Dussel describes that, the idea of the future that was casted onto the Americas in the 16th century and 17th centuries, was one where the Americas were, actually simultaneously both, outside of time and behind history.

AYESHA

Mhm.

SARA

So, it is with the premise of being outside of time and behind history, that we kind of find ourselves crafting idea of an idea of the future, that has nothing to do with, kind of, theological time, historical time, modern time, or colonial time.

AYESHA

Well, I think, like, one of the things I was thinking about was, we're sort of in this moment of the soothsayers of our times, who are the scientists, are constantly telling us it's the end of the world. It's like on the street. It's in the air. It's all around us, right? So, the, we are in end times. And yet the world continues, in this sort of, as if it's not, right? Even though the weather is all wrong. But, I was thinking about how the 16th century is the beginning of the Renaissance, right?

My earlier research was thinking about prehistories to images of modernity. So, these kinds of tropes of modernity. Like the city, or the city as hell. I was working a lot with Walter Benjamin, but what I was doing was, I was tracing a lot of prehistories to late Medieval, Early Renaissance. And finding these moments in history that kind of anticipated the images of 19th century modernity.

And one of the things that struck me was that, you know, people were way more imaginative. I know this sounds like a bit of a facile thing to say, but I think because there wasn't such a division between the sciences, the astrological and the astronomical, the natural sciences, religion, spiritual belief, that they had, kind of, more articulated tools around thinking about things cosmologically. So, I'd never thought about the new world as, literally, their version of the new world. So, like the way science fiction today, or early 20th century imagined other planets as this foil, they still had parts of the world that were uncharted enough to re-imagine things.

And it also made me rethink something which I've written about a long time ago which was, um, you know, the significance of monsters on maps, and the whole iconology of borders on maps in the Early Renaissance. So, yeah, that's what it made me think about. But just that, in this way that, so crisis necessitates new tools,

SARA

New images.

AYESHA

New images. And then those images have to do some work, right? And the ways in which you talk about what the Americas are doing, in the sort of imaginary of Europe, they're doing that work, right? Yeah.

SARA

Yes, absolutely. That's exactly, yeah, why I wanted to start with this story, because it is about image making.

AYESHA

Yeah.

SARA

It is about redefining our relationship to our environment, via visual instruments, visual technologies.

AYESHA

Yeah.

SARA

And, of course, that has huge consequences for, not just the climate catastrophes that we have, but the epistemic crisis that we are facing. Where there are no room for other ways of knowing. Where coloniality has become an instrument of disavowing other forms of knowledge production, that are not ocular centric. But still, I think that in the wake of so much that is happening, and the intersection of all of this, is precisely the responsibility that we place in images. And how, yeah, it's really important for us to start with maybe vision, perhaps as one way to understand historically also how we've dealt with some of these conditions.

AYESHA

One of the things your story highlights also is the myth of seeing crisis as unprecedented. We're always in this moment of surprise. Benjamin talks about that, this constant surprise that this is where we are, in the theses. You know, the state of right-wing politics, but also in the state of, like, climate crisis, that, oh, this has never happened before. And so, in a way, there's a kind of fetishization of that horror, that undoes the critical work that says, no, this happened before, this happened before, this happened before.

You know, you said this, the term teleological, which I think is really important, because I think this very dominant narrative around history, is so much around this idea of, we're in a constant state of progression and we're at the most advanced stage, right? If we undo time, catastrophe by catastrophe, and fold them into each other, then we have a very, very different notion of time. And we have a very different notion of eco-futurity, that comes out of crisis and disaster. Do you know what I mean? Like, so, in a way, if we think about the images in the 16th century that you're talking about, we smash them with the images we have now, or we put them in juxtaposition, those are talking to each other so much more than like the intervening centuries. And this constant bewilderment and wonderment that also is a way to, kind of, shove it aside. Like bewilderment becomes a way of, not repressing it, but then putting it in the realm of wonder, and then continuing with the day to day business of living.

SARA

That's interesting. Yeah, the reason why this is also important to me, was precisely because it is about the exercise of rethinking how do we use other tools to not really think about the future, and its relationship to catastrophe or the possibility of this ending. So, one of the things that we've entered, precisely, is an age of the management of catastrophe. Catastrophe is not new to our time, but one of the things that has been decisive in the last also 30 years is, precisely that we entered in this, kind of, stage of advanced capitalism. The culmination of a, quote unquote, process that has led us into, just living into a perpetual ending. The end. The catastrophe has no end. It's just an aggregated set of catastrophes.

And the management of the end, is something that, I think also precisely, makes us think more carefully, not just about the future, but the future as being redefined as this preoccupation with the past, right? So, to talk about the future and to talk about catastrophe is really just an entryway into something bigger. Which is our preoccupation with the past, and how the past now signals the possibility of the future once again.

AYESHA

Yeah.

SARA

There's also the tools that we use to look back. Like you're saying, if you were to juxtapose some of these images, they become so much more relevant because we have to do this exercise of looking back in time. And to look, not just the proverbial other way, but backwards. To think of them and reimagine them together to, I think, make more sense of what we're looking at.

AYESHA

I think what's really interesting is that we both work on eco-futurisms, right? It's this site of possibility, but the futurities is also like this real site of danger. I'm thinking about, say, the work of Franco Berardi or Mark Fisher, who sort of talk about how there are these moments, in which, the future becomes this sort of site of possibility. And yet how quickly they become co-opted, right? By capitalism, both in its early stages, as you describe. The new world, is the new world because of the rapacious nature of colonial, like the kind of imaginary that fuels the rapacious nature of colonial expansion. And yet there is this possibility with eco-futurism that folds into eco-pastism, I don't want to say history, but something that's like alive, right? Something that's alive. Like it's this real knife's edge, like these moments open and then they get, they get co-opted. And so, I think both capitalism and anti-capitalism is doing this, kind of, dance. And one of them’s got bigger and heavier feet. I don't know how else to think about it. But yeah, maybe I'll leave it there and maybe ask you to come back to your term.

SARA

It was actually something, it's a very new term to me, so I don't have a lot of information, but it resonates with some of this thinking. And it's a term by the Bulgarian writer Georgi Gospodinov, and he was talking briefly in a conference, where he introduced this term chrononostalgia  . And it was really interesting because, of course, I think it's a loaded term to think about nostalgia. But, in the end, what he was trying to describe was that, of course, our idea of nostalgia has changed. And that following this etymology, it no longer, of course, signals a longing for home or place, but a longing for another time.

. And it was really interesting because, of course, I think it's a loaded term to think about nostalgia. But, in the end, what he was trying to describe was that, of course, our idea of nostalgia has changed. And that following this etymology, it no longer, of course, signals a longing for home or place, but a longing for another time.

And that resonated with me. And going back to the story, precisely, because it was a search for a different time, for another frameworks of telling time. Not necessarily for a return in time, even though the term seems to suggest, and going back to an idealized or essentialized idea of a better time. And that's not really what's happening, right? We see a lot of this returns, and is looking back to, to history, to the past, to memory. But not necessarily to search for a better time. As opposed to looking for a past, that has not yet passed. And to look for a time that is completely outside of linear time.

And so, the exploration of other frameworks of telling and describing, and being or existing, in very different relationships to temporality is something that resonated with me when hearing this term. But in essence, an evocation for a sort of return. And so, for me, what's interesting and provocative is, how do we return without going back to the same place? And that was something that I was left thinking.

AYESHA

Mhm. You know, one of the things I was thinking about when you said that, is that within climate justice discourses and anti-capitalist discourses, there is this danger of, like, fetishizing Indigenous knowledges. And to see Indigenous knowledges as coming from the past, and therefore more true or more authentic, or like there's some kind of unbroken line with the past. Which is a very muddy thing because, I think like, whether people are fetishizing, is actually something that's actually something that needs to be kept alive and vital, which is that of knowledge systems that are outside of dominant capitalist discourses, right? As opposed to the fetishization of, like, groups of people and knowledges, right? Or there is like these fantasies of returning to the land. There's also like fascist histories around returning to the Iand, do you know what I mean? So, I think that…I don't know why I'm on this pessimistic sort of mood right now.

The other thing I thought about when you said that, about the past having this, the past that's not a site of nostalgia, and the past that is also distinct from the present. Several years ago I was in Columbia, I was in Popayán, which is the repository of, it's where a lot of archives are kept. They have really old documents, and I went to one of the archives and they had documents like from like the era of people fleeing the Spanish Inquisition. So, the archivist took out the documents and then she said, put on some gloves.

And I was like, yeah, okay. You don't want me to damage the paper, I assume. And then she said, no, this paper is actually covered with bacteria that's going to hurt you, because it's from so long ago that it's organisms, that are not, that I wouldn't have immunity to. And then that kind of, I don't know, that really skewed for me, my perception of the past as being dormant. Yeah, to think about the past as being alive in its own kind of radioactive state. In this case, like a bacterial, irradiative state. But yeah, to think about the past in that way, to see it as alive.

TRANSITION SOUND: Frogs.

So, the clip that we just heard is surprisingly, um, frogs. So, I recorded that sound when I was doing research on one of my chapters of this project called Black Atlantis. Which is a sort of re-reading of history, of transatlantic slavery, by going underwater and imagining alliances with more than human life forms complicities with the weather. And then also following this electronic band from Detroit, from the nineties, called Drexciya, who sort of reimagined histories such as the Zong, like the slave ship Zong. Where men and women were thrown overboard for the ship owners to claim insurance. And what Drexciya did, is they imagined that the unborn children of pregnant women, adapted from living in amniotic fluid to seawater. So, they turn this moment of massacre into this really celebratory survival. And through that kind of speculative fiction, I reimagine this sort of interspecies kind of collaboration. But also to find ways to link it with more contemporary occurrences of people trying to cross the Mediterranean, and dying quite often.

And I was doing this work about years ago, and now there's quite a lot of really amazing work being done in this field. But I was working on this one chapter hot on the heels of…Do you remember this moment within climate crisis, where there was all these ‘cenes’? What was it called…the Capitalocene, well, the Anthropocene. But then it, like, kept on spurring newer ones and newer ones. And then Anna Tsing and Donna Haraway came up with this term called the Plantationocene. It was like the devastating effect of the plantation form of production, and the way in which they, kind of, attempted to perfect the complete mechanization of men and women to work on these fields, to produce this kind of perfect crop.

So what I did is I spent two months in the Caribbean, a month in Trinidad, and a month in Barbados, thinking about, because Tsing and Haraway go very quickly to the present moment around monocropping. And what I wanted to do is, I spent quite a while on a former plantation. So, I wanted to think about the persistence of traces on a natural plantation, in terms of climate change. But, the first thing I heard when I landed at the airport were these frogs. And they sound to me, I just thought, I was, like, looking out in the fields and I was like, I don't really know what's going on. I think this is, these are car alarms. I had no idea. And so, there was this weird sort of, I don't know, collapse of human production, non-human. Maybe I'll stop there because there's ways in which I've used this, the sound in my work, but maybe I'll leave that to you to, in case you want to say something.

SARA

I mean, I definitely love what you were talking about earlier, about the Atlantis and looking at these moments of death, also as a moment of rebirth and adaptation. Especially like a multi-species adaptation, and to see the ocean as a site for some of that, a transformation to come in. Because I think it also dismantled this idea of humans, people walking the earth and being land locked into some degree. And for this imaginaries of us, kind of coming from fish, and being able to return to fish, to return to water. I think it's also very like fascinating and recurrent in a lot of contemporary artworks that deal with climate change and eco-futurisms actually. And precisely to do this kind of historical task, of thinking about the origin, or the moments in which some of this history is violent histories needed to be traced, needed to be reimagined.

And that's a little bit of what I was going for in this chrononostalgia  . It is not necessarily a longing, but a need to look for the past, and to rethink of it and re imagine it. Creating these images, I think, for ourselves to associate the possibilities of escaping these chronologies of domination. So, instead of just being stuck in the sad, detrimental, and terrifying past, to grapple with the possibilities of re-existence, that it enables.

. It is not necessarily a longing, but a need to look for the past, and to rethink of it and re imagine it. Creating these images, I think, for ourselves to associate the possibilities of escaping these chronologies of domination. So, instead of just being stuck in the sad, detrimental, and terrifying past, to grapple with the possibilities of re-existence, that it enables.

AYESHA

Mm-hmm.

SARA

And to use our imagination, to use our interest in the very interdisciplinary and collaborative imagination, to redefine, I think, the possibility of even the future to exist. But a multispecies future for that. But tell me more about the frogs.

AYESHA

Haha! Yes, I was literally walking past former settlements where enslaved men and women live on the property. But with the frogs, I think there was something really uncanny about them. And no one thought twice about them there, because it was just a part of what you heard at night, at dusk.

I used the sound of the frogs in two works. I made a piece called A Transatlantic Periodic Table. It was a sound work that was drew from one of Primo Levi's three autobiographies. And his was called [The] Periodic Table. And it traced his life, and his formation as a chemist, literally charted through, you know, there'd be hydrogen, helium, carving the list, and then, and then it would have a short heading. And I was invited to make this piece for a commission. And I'd been working on Black Atlantis for a while and I just, I hadn't accumulated elements, but I'd accumulated compounds. I had sugar, bones, coral, iron, I can't remember what else, it's been a while since I made this piece. But when I was in Barbados, that's a bit naughty to say this, but me and my host were like driving in Barbados, and she said, there's this abandoned sugar production factory and I've always wanted to go in, and I was like, let's just go in. So, we just went in. And it had been ditched in the 70s, and there were still beakers and ledgers, and so I was just filming with my phone. And so, the section on sugar had the sound of the frogs. But everything was broken, and the stairs were eaten with termites. And then there's the sound of the frogs. And they're just there, because that's just what was there. So, you see it's very dark in the building, you can see these flickers of light, and we're walking through.

And then several years later, I made something for, not the last but the one before, the Liverpool Biennial. The project was thinking about the first undersea cable that was made, and that was made between India and Great Britain. It was laid down, or it was precipitated by this huge insurrection in India against the East India Company. But because communication systems were so poor, it took six weeks for Great Britain to find out. The telegraph cable was invented not long after, or they started working on it not long after electricity was developed. So, it was this, kind of, new thing anyways, mid 19th century or so. And it was a sort of dalliance of like the Elon Musk’s of its time, you know? Just like rich people pouring money into it, and then trying to, like, lay cable. But then they got serious, because this was, like, empires at stake. So, Britain took over the East India Company. And then within 20 years, they had a cable going from Great Britain to India. Because they were still even figuring out how to make a cable, let alone an undersea cable, there were all these experiments. And then they found that the most inert substance they could find to coat the cable was a kind of resin that was extracted from Southeast Asia, from Borneo and Sarawak, called Gutta-percha, a kind of latex. So, it was this really early instance of globalization, because Chinese traders were involved, who were addicted to opium. Indigenous peoples were extracting the latex that Gutta-percha is traded.

Basically, the only way I could figure out how to tell the story was to, kind of, imagine these forests at the bottom of the sea. So that's what the installation is. And so, I was working with a sound designer, and we were trying to figure out what it should sound like. Should this underwater forest sound like it's underwater, or should it sound like it's a forest? And we, sort of, decided it should sound like a creepy forest. So, we worked with a vocal artist who was making these, kind of, guttural sounds. And it was like nine channels of sound. Like four speakers on the outside, four in the middle. And then these long panels with textiles, with prints of these trees, archival prints of these trees. But the frogs somehow came back there. And I think when people hear it, they think they're birds. I was kind of okay with people thinking that the frogs are birds, because it's such an unearthly sound and that's what we were going for. The piece was called I sing of the sea, I am mermaid of the trees. And so, there's this witness, who's this mermaid. Who's looking at these trees. But then, I think part of it was also thinking about, how frogs are also real indicators of, like, climate disaster, aren't they? Like, aren't the rainforests going quieter? Aren't there, if the frogs are louder, if there's more frogs? That's a sign of a healthier biodiversity.

SARA

That actually reminds me of my sound piece. It's actually, maybe, a joint story of another reptile.

AYESHA

Amazing!

SARA

Another type of invertebrate! The story of a snake.

TRANSITION SOUNDS: Amantecayotl Sounds

SARA

So that's a, the clip of an exhibition that I curated recently called Āmantēcayōtl, which means technology in Nahuatl. And it's by this Nahua artist, Fernando Palma Rodríguez. And Fernando has been making these robots since 1994, and so this is, kind of, the 30 year anniversary of some of his knowledge and thinking around indigenous technologies.

But the sound that we're listening to, is of the cincoatl snake, which is, like, the main piece of the exhibition. And Fernando has told me a lot about the snake. Of course, the snake in, kind, of Aztec and Mesoamerican iconographies, is really recurrent across manuscripts and murals and temples. So, it has a variety of significations, and it means very different things and a multitude of things for, you know, Aztec, ancient Aztec and Nahua peoples to Maya peoples in the south.

One way to think about this snake that we're listening to is, as the farmers call it, which is the snake friend of corn maize. So, the snake is also allowed to roam the crops precisely because it, kind of, keeps the rodents away. Protecting the harvest of corn, of the milpa. But in cosmological terms, among some other kind of ideas, the snake also signifies time.

And in this particular exhibition, this is, kind of, a two headed serpent. And what is beautiful about the serpent is that it encapsulates a lot of Fernando Palma’s ideas on technology. Because of course he's, kind of, reading the sigmoidal shape, or the S shape of the serpent to be an indicator of the ways in which now, Ancient Aztec peoples would have read also the principles of quantum mechanics. But in the, kind of, calendar interpretations of the snake, and how the snake appears in Aztec calendars, the snake precisely, even though it is associated with this idea of cyclicity, is not a full circle. It's thought of to be this deity, this sacred deity, representative of time, precisely because of it’s S shape.

So, you never, despite these ideas of birth and rebirth associated with the cycles of the harvest and the cycles of the calendar, the turn of the sun and the moon. The serpent's shape is not a circle, and I love that. I love the fact that he, kind of, continuously hints at these ideas of the openings of time. And the ways in which the serpent itself, can associate and be also perceived as a figure of adaptation, of transformation. Yeah. Of becoming something of new ages, new turns in time. In the exhibition, the serpent is actually broken. There's the two kind of heads that are coming from the ceiling, but the body of the serpent is kind of shattered. And the entire circuitry of this electronic kind of robotic work is the serpent moves constantly to rebuild its own body. To turn time back to it’s, kind of, balance from a time of destruction, into a time of other forms of cycles, other forms of telling time.

But what caught me, and this is why I wanted to respond with this sound piece to what you were saying, is precisely these early ideas of electricity. How we find some of these imaginaries of electrical waves. And there's something beautiful that Fernando talks about when associating the snake with quantum mechanics. And he talks about, that we're all in an electromagnetic sea, that we are all electricity. It is not just this kind of principles that gives light or powers the world, but that we're all in the field of electricity. We're all electric beings. I think it brings us back to some of the ways in which we would relate to each other and to the environment. In a relationship of reciprocity and exchange in which we're, kind of, quite dependent. Depending on our own electromagnetic fields.

AYESHA

Oh I love that! We're all in an electromagnetic sea. That's amazing, that's a beautiful image. I mean, it's interesting because when I heard the sound, it made me think of clocks and like the mechanism of watching, like, the rattle. So, it's interesting that what I'm hearing is, like a kind of, kinetic sculpture producing that sound, that's actually for a creature, that's actually undoing time.

I was thinking about that, what does it mean? Because you said that the body of the sick is fragmented and it's trying to mend itself. But it's like, what does that mean if mending time is not linear time? Like, what is mended time? Because it's not going to go back to linears. And if it's not going back to linear time, and time itself is in flux between catastrophe and repair, between undoing and redoing, then what is it? A restoring of a kind of cycle between them? Or some kind of movement, right? Like some kind of like dance through different intensities. Whether they're intensities of non-events, which are really important in life. And then those that are more spectacular. What do you think? What does that mean? What does amending time mean?

SARA

Well, I think it's less about repairing linear time and more so, I think, going back to the original story. To find other ways of telling time. To repair those other forms of telling time that have been disavowed as legitimate forms of telling time. So, it is not necessarily fixing a, kind of, colonial modern time that led us to a particular kind of breakage. But the perception that other ways of telling time, and other ways of world making, have also been collapsed and broken. I think it's more of that exercise of a particular, I don't wanna say rediscovery, but yeah, rethinking of other forms of telling time. And its possibility for the value that they have, in addressing some of the current catastrophes that we face.

AYESHA

Repairing the stories of time, right. And then, you know, the telling of it is the recounting. But then it also, because it's the snake, raises the question of different ways of telling time. As in what species, what elements also narrate time?

TRANSITION SOUNDS: Amantecayotl Sounds

I was thinking, Sara, about, yeah, like we're in this sea of electromagnetic, magnetic impulses. And, you know, I guess all our internal organs also function. Like, not just our brain, like our synapses. I think actually, even how we digest and how our heart, the echocardiogram, everything. We're just a compendium of, like, electric impulses. And so are possibly, like maybe, that's like how other plants, and both flora and fauna are in this field, you know? The great, but not just externally, but just internally. Like the, kind of, complex lives that are within us as well. They have the same diversity, don't they?

SARA

Mhm, absolutely! And I think it's about reckoning something that is really obvious, I think, to some of us at this point. But it is the multi-species quality of, also those temporal regimes, not just in geological terms or scientific terms, the ways in which we understand species. But the ways in which we can attune, even to our own organicity, and our own cycles, and the cycles of other living beings in having other ideas of, not just of time, but of being and existing in the world. And that's also where the serpent has become really significant for this installation, but also for the thinking and a practice of being that the artist develops in his own hometown. What I mean by that is, that going back to this idea of the snake friend of corn maize, right?

AYESHA

Mhm.

SARA

For the milpa, for the harvest to happen, the serpent also has to have a role in his electromagnetic field. Has to operate also, to allow other cycles of life to happen, other forms of growth and decay and repair.

AYESHA

Yeah. I was just thinking about then, that brings us into cyclical time. And also, just this idea of, it just changes what time is, isn't it? It's scalar and it's organic. I think of electromagnetic time as somehow organic as well. It's not just electrical impulses, but that are within an organic, sort of, spectrum rather than the scientific predominating. Which sort of, I think, takes me back to something we were talking about at the beginning, which is around like a renaissance. Medieval, imaginary, which also had a larger set of images with which to understand some of this, these conceptions of time as well.

SARA

So, what was your term?

AYESHA

Aha. My term was, um, was really simple, is the subaquatic. And the reason why I came to it, was just because, to imagine things underwater as they are, but also to imagine things that are not usually underwater. Underwater produces, like, all these possibilities of rethinking time. So, like, the ways in which futurity has a kind of traction on the wheel. So, you imagine a future and then it, there's a moment of possibility, right? So, like with I sing of the sea, I am mermaid of the trees, is taking this history underwater, and then imagining what could happen there to that history. And then, if you have this kind of episteme of the subaquatic, you could take the subaquatic above the water. And by that, I mean, how does that change how we experience things like the rain? Or ocean currents which is actually really the wind?

While I was in Barbados, I came across a kind of shrine. And then I was talking to some friends about it, and they said, oh this is a shrine for a migrant ship that was trying to cross the Mediterranean that ended up here. And basically, what had happened was, that people had set sail from around Mauritania, and they were trying to go to the Canary Islands, which is the Spanish territory. The ship went through all kinds of troubles and then people lost track of it, and basically it then drifted. It just drifted to Barbados where it was found four months later. Everyone had died. But there was somehow, the combination of the seawater splashing on board and the sun and the rain actually preserved the remains of people who had died on board. So, there was this way, in which the weather was a really, really huge character in the story. You know, the story wouldn't have been the same. And it also, for me at least, collapsed kind of historical timescales, because it was exactly the same currents that would have taken ships full of men and women centuries before to Barbados. So, it was, like, the first natural port of call from West Africa. Yeah, so the subaquatic, I felt, is that kind of environmental cue with which to unravel and rethink these histories from a slightly different perspective.

Transition Sound: NASA Voyager Space Sounds – Saturn

AYESHA

Before I tell you what it is, do you want to venture a guess, Sara, as to what it is? Or what did it make you think of? Maybe I don't want to ask you to guess, but what did it make you think of?

SARA

You know, it kind of brought me into this very immersive experience. Maybe because I was listening to this aquatic feeling. Like maybe it was in an environment that also holds a very similar kind of chamber effect. Where you hear something, but you're also, kind of, turning to your interiority. So, we really then, the beating of the heart, and other kinds of indicators, I think become prominent as you enter a chamber of vacuum of sound. That seems to be, like, a little bit of a hallow sound, but underwater. Like that experience of going under something. So that was my experience. The listening is really important, but it triggers other forms of, I think, experiencing the body.

AYESHA

Yeah. It was fun watching other people in the studio listening to it, because everyone had their eyes closed and they were nodding and fear speaking, which is really nice. Actually, the sound, I downloaded it from NASA's Halloween themed page, so it's open source. But what it is, is it's a, kind of, sonification of data, received from a satellite projected onto Saturn. So, what you're hearing is the sound of Saturn's data. And on Instinct, I've been collecting these sounds for a long time. And I guess there's a few reasons why I brought it here, because there's this kind of interesting, just as we've talked about collapsing, or like the kind of infusion of the past and present and different temporal moments. There's a lot of sort of interplay and interpenetration of outer space, and is sort of much more charted than the bottom of the sea. So, we know much less what's going on in, say like, the Mariana Trench than we do of where Neptune is. But the sound has found its way into a lot of works I've made. But most notably I made a performance, I call it a live PowerPoint essay. So, I take a really crappy technology like PowerPoint, and then I soup it up with a lot of sounds and videos. And then I, I sort of do a live reading. And I told the story of the ship, that was called The Ghost Ship in the news at the time, in 2006. And my own experience of discovering it. And then, sort of around the same time, I was invited to make a work for the Dakar Biennial. And what the curator had done, is actually, he introduced me to a Mauritanian Senegalese artist named Hamedine Kane, who himself had crossed the Sahara, and walked, and then crossed the Mediterranean. And had, by that time, had received asylum.

So, we made this film together. And the film is in part about the story I just told you and it's called In the Shadow of Our Ghosts. But the other part is about his experience of time walking in the desert. Its him recording, literally just his shadow and his feet, walking across different terrains. And he's reciting, again and again, this text that Édouard Glissant wrote about the kind of, event of people crossing the Mediterranean. And it's a kind of list, a list of like, the libraries of Timbuktu, bananas. And he just, and he repeats it, and he repeats it until his mouth dries, and you can hear him swallow.

But we start the film with this sound, because there's a lot of images of water. We were both in Senegal at the time. We were both shooting lots of images of the sea and trying to imagine the ungraspable horizon of the sea. And we come back to this sound repeatedly.

Transition Sound: NASA Voyager Space Sounds – Saturn

AYESHA

I think that there's what you talk about, like this kind of, like interpolation or this kind of, pulling of, at the heart. What I'm doing, is I'm kind of rationalizing a choice to put the sound in this film, and in this project. But really what it was is that, because that story is so horrific, but, I was trying to find a measure of how to think about abstractions, like the weather and the rain, and kind of, speculative things, but keeping the gravity of it. So, thinking about like non-human witnessing, non-sentient witnessing, that doesn't turn the speculative into something like, hey wow, Sun Ra. But you know, like something that's outside and inside. Like a kind of outside, holding space for a story that, I've actually stopped performing this piece for several years, cause I just, didn't feel like I could tell the story and be present to it. And so, I feel like the sound, and the kind of feeling of that sound, really does some of that. Makes that space.

SARA

Interesting. I wonder if you could tell me more about, like, choosing a kind of extra planetary sound as a source, and the kinds of things that that could trigger? Only because, I mean, since we're kind of talking about time and the future, even tangentially, it seems that there's so much about the future that is associated with extra-terrestrial space travel and exploration.

AYESHA

Yeah!

SARA

Which, of course, has ramifications and precedents in earthbound colonization as we've established. So, even like talking about this outside-inside, kind of forces away how you project the outside, or our inseriority into the outside. And I think extra-terrestrial imaginaries, but also travel, has everything to do with some of that as well. So yeah, the choices of thinking about sound, in this particular source, and how it maybe triggers or catalyses some of this other work that you're doing.

AYESHA

I guess. Within the kind of world of Afrofuturism, it's one of the ingredients. But I guess, I was thinking about it, I mean, in this particular work, less celebratory. In this instance, I guess I'm drawing on a different register of outer space, which is thinking about a, kind of, extraterrestrial witnessing, I guess. Maybe that's what it is. Instead of being the site of joy, which is also within the kind of world of speculation that I'm really interested in, but in this instance, it was needing something that was also a bit impersonal. A little bit like what meditation does to you. You know, a kind of warm, but yet distant, witnessing, impersonal and yet close.

At the end of the day, it was just, I was collecting these sounds, and then this was the sound that wanted to be there. And sometimes you can figure out why afterwards. But I liked that it was weird, I liked that I downloaded it from this NASA Halloween site that literally had a, you know, little gif of a jack o lantern, like very 90s style web page. I think now it's a bit more sophisticated. I think it's on SoundCloud now.

Transition Sound: NASA Voyager Space Sounds – Saturn

SARA

I was trying to maybe wrap up like by connecting some dots about the subaquatic, the extra-terrestrial.

AYESHA

And your term, the chrononostalgia  .

.

SARA

Just time in general. This kind of search for other forms of telling time. Existing completely in different kinds of realms of space and time. And maybe this is where some of this connects. Like how this, they don't have to be imagined. As in they're not outside of this earth, or outside of the historical precedence that we've had. But it is an attempt to thinking about mermaids, thinking about the ocean, thinking about even time. The past as this other world, other place in time and space. There seems to be an intent to reify some of these other places. For, in the search for, kind of also, myths of origin, complicating the story of origin, creating in essence, also new narratives for this kind of ontological becoming.

It originates from places of violence, but it doesn't reify that violence. It doesn't centre violence as much as survivance, co-dependence, coexistence, multispecies thriving. So that's a little bit of what I'm hearing us think about, as we discuss some of these listening exercises. Yeah.

AYESHA

Yeah, I think listening is really crucial, right? Cause there's a lot of undoing, right? Around like speaking for, and giving voice to, these are all like colonial extractive practices. And so, I think listening, and really listening, like listening, like deep listening, and silence, I think it is, sort of, one of the most important things that need to be done now. Or also like leave things at the moment of encounter, without trying to understand. Cause I think overly understanding things also is a bit like, a bit like hubris or something, you know?

SARA

Yeah, I agree. There's a lot of, to be said about listening. And maybe going back even, to these ideas of the ways in which we are meant to, or not meant to, but tend to, reimagine our relationship to the environment through images, and have done so historically. While leaving aside other forms of communication, senses and other sensoriums, other orientations, for building and reimagining that relationship. And listening, and attunement being one of huge importance.

AYESHA

I kind of feel like in a way, we're just starting this conversation.

SARA

Usually happens that way.

AYESHA

It's been so nice speaking to you.

TRANSITION SOUND: Frogs.

MARTIN

Thank you, Ayesha and Sara for this conversation and for inviting us to listen to the sounds of your practices. For the transcript of this episode and links to resources mentioned, go to rosechoreographicschool.com. The link for this page will also be in the podcast episode description wherever you're listening right now.

If you'd like to give us any feedback, give us a rating wherever you're listening to this. Or email us on info@rosechoreographicschool.com. This podcast is a Rose Choreographic School production. It's produced and edited by Hester Cant, co-curated by Emma McCormick-Goodhart and Martin Hargreaves, with additional concept and direction by Izzy Galbraith.

Thanks for listening. Goodbye.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Projects and Publications:

A Transatlantic Periodic Table – Ayesha Hameed

Black Atlantis: Retrograde Futurism – Ayesha Hameed

I sing of the sea, I am mermaid of the trees – Ayesha Hameed

ĀMANTẼCAYÕTL – Sara Garzón (and Fernando Palma Rodríguez)

Black Atlantis: the Plantationocene – Ayesha Hameed

In the Shadow of Our Ghosts – Ayesha Hameed and Hamedine Kane

Books and Texts:

Dussel, E.D. (1994). El encubrimiento del otro : hacia el origen del mito de la modernidad. Quito, Ecuador: Ediciones Abya-Yala.

Haraway, D. (2016). Staying with the trouble: making kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press.

Levi, P. and Rosenthal, R. (2012). The Periodic Table. London: Penguin.

People:

Historical References:

History of Astrology in the Renaissance-Great Conjunction of 1524, Height and Decline of Astrology

Medieval Maps and Marginalia: Monsters and Hidden Meanings – The Historians Magazine

Other